Nominative Determinism

Writing names and crossing them out again...

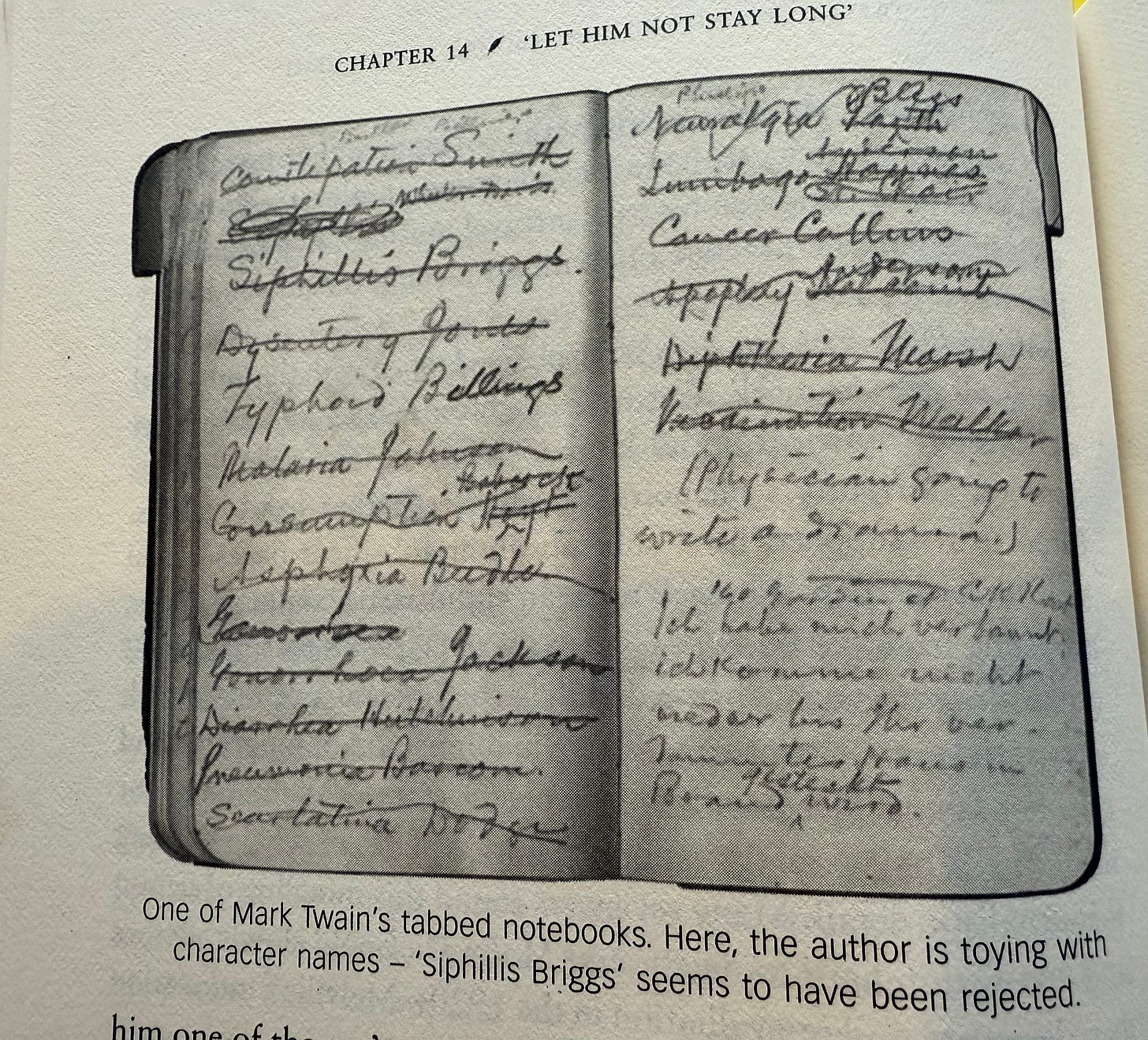

If you’ve ever struggled to come up with a perfect character name, you’re not alone. I found this gem in Roland Allen’s The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper, showing that Mark Twain had his write-a-line-and-cross-it-out days too:

Malaria Johnson! Asphyxia Beedle! Diarrhea Hutchinson! Siphillis Briggs! Poor Cancer Collins: the most unfortunate superhero name?

I recently read the first book in Derek Landy’s Skullduggery Pleasant series, in part to check its bedtime reading potential, and in part because, as a person with a professional interest in skeleton wizards, I’ve been derelict in leaving these on the shelf for so long. It’s fun to read a book at 40 and enjoy it a great deal and at the same time to be keenly aware how much it would have rewritten my personality if I’d read it when I was 10. (Maybe. I’d already been fully occupied by Lord of Light and The Hero and the Crown at that point…) If you’re looking for magical wisecracking skeleton wizard fighting adventure books that are perhaps just shy of what we call YA these days—and if you’re not, I question your life choices—give these a shot.

Anyway, names: one of the ways magic works in these books is via good old Earthsea true-nomenclature. Call something by its true name, and you have power over it. Most people don’t know their true name, so this is a difficult attack vector. Don’t relax yet, though: a person’s given name, the name they’re assigned at birth, can also be used to control them. If the Bad Guys have a phonebook, you’re in trouble.

Fortunately, wizards have a special third name, a chosen name, a name they find themselves. Once you choose a name, your given name is sealed—and useless for conjuring purposes.

A few thoughts:

It’s a nice, neat system, and a great way to show character growth.

This smacks of gender, as the prophets say.

Most delightfully, at least to your humble correspondent—this gives a perfectly defensible and logical in-world reason that all your wizards have utterly bonkers wonderful style-dripping all time trapper-keeper hall of fame names like Valkyrie Cain, Sagacious Tome, Mr Bliss, Skullduggery Pleasant, Ghastly Bespoke, China Sorrows, and Tanith Low.

Extra style points for the fact that the mad-bastard elegance of #3 didn’t even occur to me until a week after I finished the book. This system could have been a sort of nudge-nudge-wink-wink bit of world-building satire, but the book plays it completely straight, to the extent that it’s a big sky-punching moment when our main character chooses her own name—but it’s also fun to imagine Landy hearing a reader complain: why does nobody in this book have a name like Bob or something? and thinking, well, why not?

The new pope seems cool.

Everybody seems to be thinking a lot about LLMs these days and so am I; it feels dangerous to start writing about the subject for fear I won’t be able to stop, but I have noticed a pattern.

One reason folks seem to turn to LLMs for text and image generation1—folks who are aware of the tech’s limits, that is, not the surprising number who really should know better2—is to produce work they deem fundamentally worthless. A bit of ad copy, a placeholder paragraph, “this stock market article needs a picture for SEO but I don’t care what it is or if the market bull has six horns and three legs,” etc.

Now, there are lots of reasons for writers and artists and thinking persons to regard these technologies with suspicion—or rather, to regard the people who boost and build and deploy them with suspicion. They are absolutely being used against workers, as a lever or a threat even where they are not practically useful as a replacement; and of course Meta seems to have used a pirated database to grind a dozen of my books (and everyone else’s!) into their pink slime machine.

But the disgust I see (& sometimes feel) for this sort of LLM usage isn’t all or even mostly traceable to sublimated class unease. If you’ve developed a skill, you care about that skill. I can’t think of the last time I wrote something I thought was pure throwaway text. If I realized that was what I was doing, I stopped and wrote something better, because that’s the way. The thought that someone wouldn’t give a shit about their own work, or about the readers of that work, is alien. Add to that, the fact that writers & artists tend to be small businesspeople, and small businesses are built on relationships—someone who regards their business communications as throwaway and insignificant is unlikely to last long.

LLM text generation, then, seems like a boon for checked-out cube workers or “eh-good-enough” types in meaningless roles, churning out below-replacement-value text—which are exactly the roles most vulnerable to its deployment in near term; it’s a weird feature of this technology that the more neat and useful you find it in your daily life and work, the more likely it is to come for your throat.

I should be outlining today, so I’m going to get back to it. This month on the Craft Countdown we’re re-reading Full Fathom Five! And if you’re looking for a game to play that may mess you up and get you to think about death and feel sad and stuff, do consider Clair Obscur. I played the first hour yesterday in a rare moment of rest and what an experience. Also: so profoundly French, the most French piece of media I have seen since Elevator to the Gallows. And, for those of you that have played the opening already: I don’t think I’ve ever seen a video game use subtext like that sequence down to the harbor. (I love games and they are & can be great art, but most games I’ve played seem to share Garth Merenghi’s opinion on the subject.) Gustave, Sophie, the kids—heavy, powerful work. What glorious things art can do.

As distinct from coding. The folks I know who find LLMs genuinely useful and transformative are for the most part mid- to senior-level devs, for whom the ability to say “genie, write me test code for this particular edge case” is Really Cool Actually.

The thought that someone who had gone to law school would use these things to write a legal brief…

On LLMs -- I would add there is at least one other reasonable use case: chatgpt o4-mini-high with search is decent at websearching for and summarizing information on mundane topics that many people know well, few people disagree about, and you know nothing about. Like, if you want to know what kind of soil type is good for your nasturtium. Or if you want somebody to explain Gaussian splatting. Of course it does make mistakes, but I probably would too. In this context, it is probably ok if the quality of the writing is meh, because you just want to know how much perlite to add to your potting mix without going to a website that accosts you with a mind-numbing panoply of ads.

Of course, this raises a question about how the internet is going to actually be funded in 10 years if those websites cannot figure out how to get revenue...!