I missed last week because of travel, so here’s a surprise early-week post! I won’t be around Friday because ReaderCon, but if you’re in Burlington, MA this week, drop by and see me. You can find my schedule on the ReaderCon website. I haven’t been to the Burlington Marriott since renovation but it looks like there’s an outdoor seating area in front of the hotel—I’ll be hanging out there after my reading, 4pm on Saturday, if anyone wants to say hi.

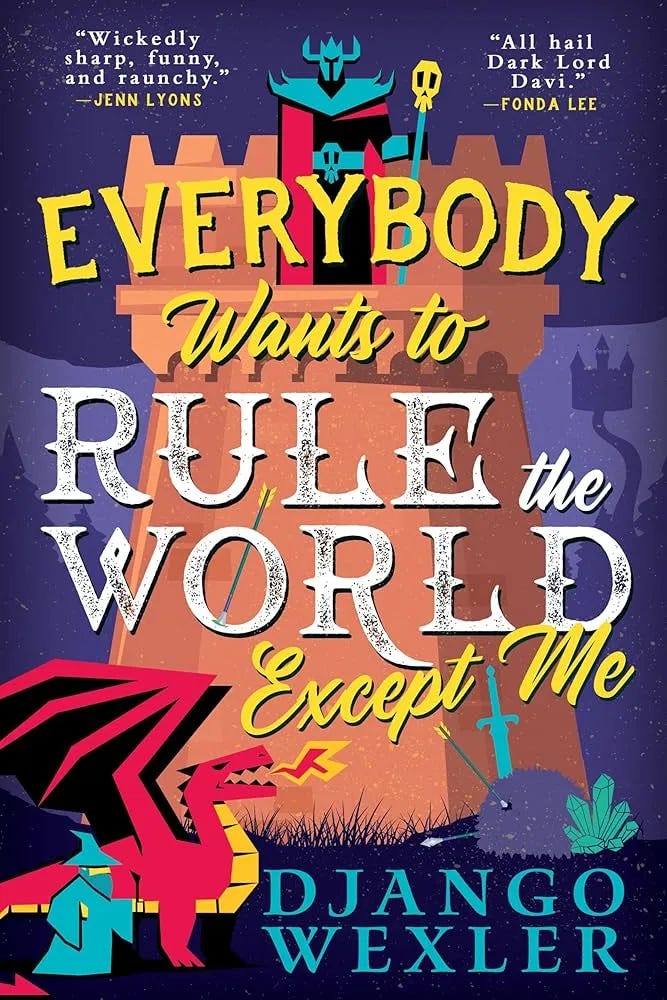

And here’s the second part of my interview with Django Wexler about Everybody Wants to Rule the World Except Me—outlining and gear discussions ahead!

Django: Do you have any other important questions?

Max: Important questions! *sweatdrop* Let me see. Well…

Django: You don't have to!

Max: There must be something! Well, I'm trying to figure out how to phrase it. As somebody who is trying to land a fantasy series right now…

How do you do it? And how did you think about it?

I mean, you're a standout in the field in that you have actually finished many series.

Django: I try, yes. I tell people this. When they're like, I don't read any fantasy series that's not finished because I got burned by George R.R. Martin. And I'm like, look at my track record. I have finished a lot of things.

It's hard!

This one was actually easier than most because it was relatively reasonably scoped and sort of designed from the beginning. Like when I pitched this series, I pitched it as three books, and the first book was supposed to be essentially all of what ended up happening. It was supposed to be: by the end of it, Davi has made peace between the Wilders and the Kingdom, and then like, I sketched in something about, oh, there's some threat from another quarter and she has to like blah, blah, blah. And then I was like, this is dumb and is like not, it's just not related to the central concept, to this time loop concept.

And, then I started outlining book one and it was way too long. So I talked to my editor and she's like, well, why don't we just do a duology? And I'm like, that makes sense because there's a really natural break point, you know, right in the middle. So that's kind of how we ended up here. But so that meant my scope was very well defined from the beginning.

So like, you know, the best hint to finishing series, and I don't know if this applies to you specifically—

Max: *laughs nervously*

Django: But in general: know where you're going and how long you hope to take to get there. You know, and outline. I outline. Not everyone has to outline, but it does help you get to the end of things.

Max: Lord knows. I wanted to talk to you about that, too. Sometimes when I have outlined books, I have found the scope… Well, It's very easy for me to write a check, a plan, more complicated than my ass can cash… or more complicated than the reader is able to follow. I can put together wheels within wheels within wheels within wheels, but then the reader has to track so many different related plot threads, levels of reality, all sorts of silliness. It's tricky.

Django: I know that challenge.

Max: So how do you handle that?

Django: The real skill of outlining, the real thing that you have to learn to do is to read the outline version of something and kind of generally imagine what the final text will look like.

Not specifically, because otherwise it wouldn't be an outline. But just sort of get the idea of like, okay, this is a fight scene, here are the beats, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah .

You know, at this one sentence per paragraph or page level of detail. This is how it works for me at least.

If I can't do that, that's a sign that something is wrong. That the scene is too complicated or my outline is not detailed enough or, you know, I think of them as potholes, which is different from plot holes. There are potholes: you get to a scene, you know, you're churning along in your outline and you get to a scene that's in the outline that's not a scene. And then you fall into the pothole. It's like a sudden stop.

Like, my example is always like, if I write, you know, Bob and Jim become friends. That’s not a scene.

Max: Right.

Django: It's not a description of what happens.

Bob and Jim go to the bar and bond over their love of old country music—that's kind of a scene. That's closer.

Bob and Jim go to the bar. Bob puts on old country music, and Jim says, oh, I love that song. And then they discuss. That’s a scene.

Max: Yeah.

Django: Because like, you know what is, what is actually going to happen.

Max: And they get into it with number three at the bar who doesn't like Townes Van Zandt.

Django: Right, exactly. Like, you can't write out, you know, Bob and Jim become friends. At best, that's like a summary. And an outline is not the same as a summary. It's not necessarily meant to be readable in the conventional sense.

So that's like part of an answer. If I can't envision how I'm going to convey this, then I don't write it. I know that in the outline phase, something is wrong that I need to change it.

But, you know, again, that's just me. Some people do better. You've read Dungeon Crawler Carl, right?

Max: I haven't yet, actually. I need to.

Django: Oh, you should read that.1

But like Matt Dinniman, man, I've had several events with him, so I hear him talk about his process. He just makes it all up as he goes along.

He holds polls on his Patreon where the people tell him what to do. I’m just like, you are a crazy person. And it's so good. The results are so good. But he also said for his latest book, he wrote 800,000 words and kept like 220.

And I'm like, okay, that's that's crazy. I could never do that. I do the outline specifically to avoid writing a bunch of words that I then have to cut.

Max: It's a hell of a style.

Django: Well, you do a lot more passes than I do. You've talked about being on your 13th pass through a book.

Max: Yes.

Django: And I'm lucky if I do like three.

Max: I think that's fantastic. I mean, I try to aim for a sentence-level precision that requires those passes… but sometimes then I pick up the book in its published form and see some real howler on page 78 and, like, oh, yikes, how could I've ever missed that? But that's also part and parcel of the whole experience.

I’ve gone through many different stages when it comes to process. It used to be I would just write the damn thing from start to finish. Often there would be a point about a third or a quarter of the way through a project where where I would sit down and say, oh, okay, what have I been writing? How do all of these different lines and threads and scenes converge?—and then I'd sketch that out and have an outline for the back half of the book. A little bit of discovery and then a little bit of improvisation and then planning, and then you go back through and make it look like you knew what you were doing the whole time.

Then I had a few books where I had to outline completely, collaborative or IP work mostly, which was… Eventually I found a really solid form for it. But then sometime around when our son was born, I had real difficulty sitting in front of the computer. Basically, the only way I could write was longhand. Pen and paper.

Django: I remember you posting about that.

Max: Yeah, and I did that for a handful of books and it worked really well…. Well, anything that gets words down on the page is better than anything that doesn't. I can look at an outline or a blinking cursor for six hours, and if that's not moving me forward, it's useless .

It's not entirely true, I guess. You know, there's work that is done, even if words are not flowing. There’s cognitive work being done.

But.

Django: Still though!

Max: Yes. Those zeros on the spreadsheet really add up.

Django: I don't keep a spreadsheet for that reason. It's too depressing.

Max: Neither do I, actually. I'll think of it at most on a day-by-day basis.

I hit on this formulation sometime last year when I ended up getting really overly invested in fitness and running metrics, like VO2max progression and all that kind of stuff—which, you know, these are real pieces of data, I suppose, and they tell you something. But it occurred to me that every metric is sort of just a codified anxiety.

Django: *laugh of recognition* Oh, no! That's so true.

Max: I think writing metrics are absolutely that way. You know, you have I need to write a 1500, 3,000, 250, whatever your number is, words a day, in order for it to mean something. Why? You don't actually! But, you know, it helps you assuage the anxiety—helps me assuage the anxiety.

Django: I would say for me, writing metrics have two purposes. The first one is like, there's a little bit of the whip in it, right? Because like, you know, would I rather just play video games instead of writing? Probably!

Max: Yeah.

Django: Some days, for sure. And, you know, there's a certain amount of writing… sometimes it's great and the muse is there and everything's flowing. But for novels in particular, there's a certain amount of writing that just has to be ground out. There are days when you're not feeling it or parts of the book that you have to get through. And, you know, having the guy with the whip there can help a little bit.

But also it gives me permission to be done? You know, this became a real problem when I started working from home and sort of doing writing full-time is that I'd start writing. And then I'd be like, well, there's like four hours left in the day. I ought to write more.

And then I'm like, I really don't want to. I feel burned out, blah, blah, blah.

And finally, I was like, okay, I got to pick a reasonable length of time to do the book, divide the word count by that length of time. And then that's my quota.

And when I get the quota, then I can fuck off for the day, right? If I get it done quick, great. I can go outside, I can play video games, whatever I want. And that sort of freedom from the ever present guilt of “you should do more” is an important factor.

Max: It's powerful, yes. Yes!

Max: When I was writing longhand, one of the advantages of that was that it takes so much longer to write a scene that my brain was running ahead of the hypothetical cursor and reformatting the scene or reworking the scene several times in the course of getting to done and thinking a lot about what was going to happen next.

Django: That's true.

Max: The scene to scene cohesion was really strong and the characters had a lot of opportunity to show off or to express their voice—again because: when you have two partners in a conversation or in a fight, if I'm working on one section, then the other has a really, has a much longer time to formulate their response.

Django: That's interesting.

Max: So the conversations got really tangled and dense in a good, sort of strong cross-linked way. The challenge was the larger arc stuff, which usually I was able to seeing at a glance when you glance at your Scrivener binder or skim through the manuscript. That kind of oversight was much harder to achieve longhand—so I ended up having to spend a lot more time in revision, getting the overall arc to work, as opposed.

Django: That seems like a place where like outlines could help.

Max: Yeah.

Max: I’m going to try to meld the process now.

Django: I’m trying to think how I would reproduce that, because I can't write longhand. Like my hand won't take it. It physically cramps and dies. I had to do exactly one blue Book exam and I nearly died. I'm glad I'm not going to college now because…

Max: Oh, geez, yeah.

Django: They're coming back!

Max: Yeah, wild, wild. We predict that Cuneiform tablets are going to make a huge resurgence.

Django: I was saying if I were founding like a device business, I would make completely non-—these probably exist already—completely non-internet-connected electric typewriters that write on actual paper… because this is going to be your in-class exams of the future. You're going to come in and you'll have this, you know, full keyboard machine that just types on a piece of paper and you're done. This is your, the equivalent of the Blue Book exam, but you don't have to have good penmanship.

Max: Yeah, the Olivettis are coming back, baby. The AlphaSmart Neo.

Django: The old ways.

Max: The old old ways.

Django: Back to the mechanical typewriters.

Max: Well, the gear fetishist in me likes that anyway.

Django: Yeah. Oh, I have friends who get super into mechanical keyboards because they're like tuning the clicky sounds to make them just right.

Max: That’s a little bit beyond me, but I did have a sort of split keyboard that has the backspace on the right thumb. And I'm a very backspace dependent writer.

I do a lot of, write write write write—ope! nope! delete all of that. So I did have to replace the backspace key with a lighter pressure switch.

Django: Oh, really?

Max: To stave off incipient RSI. So I've done like the tiniest bit of that, but I do feel that you can get a little bit overboard into process when you start tinkering with those tools. There's just so many of them out there to explore.

Django: I know.

Max: As opposed to actually getting the writing done.

Django: I'm sort of deeply suspicious of any kind of excessive process in writing. Like, it's one reason I don't use Scrivner because I feel like I would be like endlessly fiddling with the folder structure and the settings. And it's like, you can have like an encyclopedia for your world and cross links and all this stuff.

And I'm like, I don't want that.

I don't want any of it.

Max: Hah!

Django: So like I use Word, which has a lot of functions, but they're mostly useless. I basically just type type in the box.

Max: I really, now that everything has a full screen mode, I’m not sure I would have ever ended up with Scrivener, but for me, the appeal of Scrivener was to just make my laptop as close to the blinkey green screen of an old Apple 2 as possible, with like no mishigas, no notifications, no nothing. That was a real killer app for me for a while.

But yeah, the feature-heavyness of it, I mostly try to ignore.

One time, last year I was working on like building a world for a new project and I started playing around with Obsidian and I got Ralph Wiggum really fast, like: oh, I'm in danger! I need to stop spending so much time in this… because you could spend all your time in this.

Since we had this conversation I have in fact started reading Dungeon Crawler Carl and it is great, more on this later.

This is great! Especially the outlining stuff, what Django said resonates a ton with me. With gaming, it's been a process of outline <> scene running. Obviously, you never want to write down word for word what you as GM are going to say in the scene -- that defeats the entire purpose of the craft -- but also just writing "and then the party confronts the trolls and they negotiate a peace treaty" can be a little misleadingly complete. Like Django, I find I have to imagine the scene playing out in my mind with the players to be confident that the outline is useful.